In our increasingly polarized world, few concepts generate as much debate as “equality.” From boardroom discussions about pay equity to political campaigns promising equal opportunity, the term gets thrown around with remarkable frequency. Yet after years of observing these debates, I have come to realize that much of our disagreement stems from a fundamental misunderstanding: we are not all talking about the same thing when we invoke equality.

Today, I want to share my perspective on this complex concept and explore why clarity matters more than ever in our discussions about what equality means and how we pursue it.

The Three Faces of Equality

When I examine equality closely, I see it operating on three distinct levels, each with its own validity and limitations.

Equality as Biological Fact

From a purely scientific standpoint, the notion of human equality simply does not hold up to scrutiny. Individuals are not born with identical strengths, weaknesses, or abilities. Our genetic makeups differ significantly, creating variations in everything from physical attributes to cognitive aptitudes. This is not a value judgment—it is merely an observable reality that any honest assessment must acknowledge.

Consider the vast differences in athletic ability we witness in professional sports, or the spectrum of intellectual capabilities that emerge in academic settings. These variations are not the result of social conditioning alone; they reflect genuine biological diversity within our species.

Equality as Social Ideal

However, acknowledging biological differences does not diminish the power of equality as a moral and political principle. In this context, equality represents our collective aspiration that all individuals should receive equal dignity, respect, and opportunities under the law, regardless of their natural variations.

This form of equality serves as the bedrock of modern human rights frameworks. When we declare that all people deserve equal treatment in our legal systems, equal access to education, or equal consideration for employment opportunities, we are making a value-based statement about how society should operate—not a claim about biological sameness.

Equality as Political Theory

Within political science, equality functions as a core theoretical concept that different ideological frameworks interpret in markedly different ways. Liberalism emphasizes equal opportunity and individual rights, while socialism focuses more heavily on addressing economic inequalities. Each theory offers distinct approaches to defining what equality means and prescribing how societies should pursue it.

Understanding these theoretical foundations helps explain why political debates about equality often seem to involve participants talking past each other—they may be operating from entirely different conceptual frameworks.

The Social Construction of Equality

The political and social dimensions of equality are undeniably social constructs—concepts created and defined by human societies to establish governing principles and behavioral norms. This designation does not make them less important; rather, it helps us understand their origins and evolution.

Consider the principle of universal suffrage. The idea that every adult citizen should have an equal right to vote, regardless of race, gender, or economic status, represents a relatively recent social innovation. This concept was not discovered as a natural law; it was developed through centuries of social and political struggle.

The constructed nature of social equality explains why these concepts vary across cultures and evolve over time. What one society considers equal treatment, another might view as discrimination, and these perspectives can shift dramatically within a single generation.

Equality in the Political Arena

Political movements and candidates frequently invoke equality to mobilize support, though their interpretations of the concept often differ substantially. This strategic use of equality language creates both opportunities and challenges for meaningful policy development.

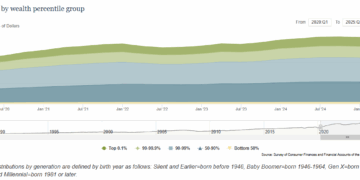

Some political frameworks emphasize equality of opportunity—ensuring that everyone starts with similar chances to succeed, while accepting that outcomes may vary based on individual effort and capability. Others advocate for equality of outcome—actively working to minimize disparities in final results through redistributive policies and systemic interventions.

These competing visions generate much of the tension in contemporary political discourse. Debates about taxation, education funding, healthcare access, and social safety nets often reflect deeper disagreements about which form of equality society should prioritize.

The Equal Pay Question: A Case Study

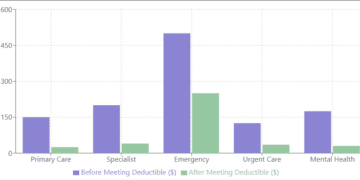

The ongoing debate surrounding equal pay illustrates how these different conceptions of equality intersect in practice. My position is that compensation should be determined by performance and contribution rather than demographic characteristics. However, I recognize that this seemingly straightforward principle operates within a complex system where multiple factors influence pay decisions.

The equal pay discussion extends beyond simple comparisons of men and women performing identical tasks. It encompasses broader questions about how we value different types of work, whether historical discrimination continues to influence current compensation structures, and how factors like career interruptions and workplace flexibility affect long-term earning potential.

These nuances matter because they shape the policies we design to address pay disparities. Solutions that focus solely on comparing salaries for identical positions may miss systemic issues that create unequal outcomes even when individual pay decisions appear neutral.

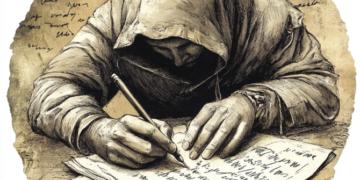

Historical Evolution: “Created Equal” in Context

The historical development of equality concepts provides crucial insight into their constructed nature. When Thomas Jefferson penned the phrase “all men are created equal” in the Declaration of Independence, the contemporary understanding of “men” was far more restrictive than our modern interpretation.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights…”

In Jefferson’s era, this language was widely understood to apply primarily to white male property owners. Women, enslaved individuals, and men without property were largely excluded from this conception of equality.

The power of this language, however, lay in its potential for expansion. Subsequent social movements—abolitionists fighting slavery, suffragettes demanding voting rights, and civil rights activists challenging segregation—all drew upon this foundational principle to argue for broader inclusion. They demonstrated how constructed concepts can evolve to encompass previously marginalized groups.

This historical progression illustrates both the limitations and the transformative potential of equality as a social ideal. While the original application was restrictive, the underlying principle provided a framework for progressive expansion of rights and recognition.

Navigating Complexity in Practice

Understanding equality’s multifaceted nature has practical implications for how we approach contemporary challenges. Rather than treating equality as a simple, monolithic concept, we benefit from recognizing its various dimensions and addressing each appropriately.

In business contexts, this might mean acknowledging that while employees bring different capabilities and performance levels, our organizational systems should provide equal opportunities for advancement and recognition. In policy discussions, it suggests the need to distinguish between different types of equality goals and design targeted interventions accordingly.

The key is maintaining intellectual honesty about what we mean when we invoke equality while remaining committed to the underlying values that make equality worth pursuing as a social ideal.

Conclusion: Embracing Nuance

Equality, I have come to understand, is not a simple concept that admits easy answers. While biological equality remains a myth contradicted by observable evidence, the social and political ideals of equality represent powerful and evolving constructs that have driven tremendous progress in human rights and social justice.

The ongoing debates about equal pay, equal opportunity, and equal treatment reflect the continuous and contested nature of defining and pursuing equality in practice. Rather than viewing this complexity as a problem to be solved, we might benefit from embracing it as an inherent characteristic of democratic societies working to balance individual differences with collective values.

Moving forward, our discussions about equality will be more productive when we clearly specify which dimension we are addressing and remain open to the possibility that different contexts may require different approaches. Only through such nuanced understanding can we hope to make meaningful progress on the equality challenges that define our time.