Look, I’ve been in this investment game for nearly two decades now, and I’ve seen a lot of folks sleeping on major market shifts until it’s too late. But the pension crisis building across the developed world? Man, this one’s different. This ain’t some distant threat we can kick down the road—the math is already falling apart, and most governments are too scared to do anything about it.

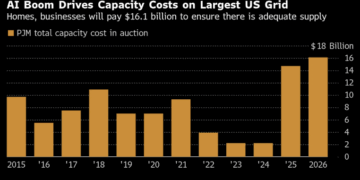

I just watched this breakdown on the global pension paradox, and let me tell you, the numbers are wild. We’re talking about a $400 trillion gap between what people need in retirement and what’s actually been saved. That’s four times the size of the entire global economy right now. Let that sink in for a minute.

The Math That Stopped Working

Here’s the deal: most pension systems around the world run on what they call a “pay-as-you-go” model. Your paycheck today doesn’t go into some vault with your name on it—nah, it goes straight to paying today’s retirees. Then when it’s your turn to retire, the next generation of workers funds your retirement. Simple enough, right?

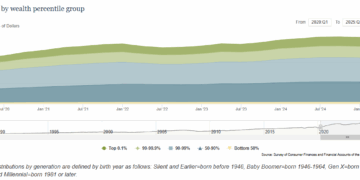

This whole setup worked beautifully after World War II because economies were growing, people were having babies like crazy, and there were plenty of workers to support every retiree. Back in 1950, the United States had more than 5 times as many workers for every retiree as we have now. Actually, the ratio was 16 workers for every retiree, and today that’s collapsed to fewer than three workers per retiree Social Security Administration CNBC.

Let me show you just how dramatic this shift has been:

| Year | Workers per Retiree (US) |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 16.0 |

| 1975 | ~8.0 |

| 2000 | 3.4 |

| 2024 | 2.7 |

| 2035 (projected) | 2.3 |

That’s a dependency ratio crisis if I ever saw one. Too few people working to support too many people not working. And remember, these numbers include all the women who entered the workforce over the past several decades, so the real change is even more severe than the raw numbers suggest.

Across Europe, Japan, and South Korea, it’s even worse. Some countries are already approaching just 2 workers per retiree. When you’ve only got two people’s taxes trying to cover one person’s retirement benefits, the whole system starts to buckle.

The United States: Running Out of Money

Let’s talk about my backyard first. The US runs the largest pension system in the world, with over 73 million people receiving Social Security, and by 2035, the combined trust funds are projected to run out of reserves Congress.gov CNBC. After that? Payroll taxes will only cover about 83% of promised benefits Congress.gov CNBC.

Think about what that means for real people. For the average American retiree living on $1,900 a month, that’s a $300 cut they can’t afford to lose. And we haven’t even factored in inflation yet—each Social Security check is already worth less in real purchasing power every single year.

But federal Social Security isn’t even the whole story. State level pension funds are in deep trouble too. As of 2022, state pensions were underfunded by $1.27 trillion Social Security Administration. In states like Illinois, New Jersey, and Kentucky, public pension plans have less than 60% of the assets they need to pay future retirees. That’s the equivalent of about 7% of those states’ total retirement income just… missing.

Japan: Running Out of People

If America’s problem is running out of money, Japan’s problem is running out of people. With a median age of nearly 50, Japan has the third oldest population on earth. Since 1995, its working age population has shrunk by about 13-14 million people Nikkei Asia IPSS, dropping from 87.26 million in 1995 to around 75 million today.

By 2050, close to 40% of Japan’s citizens will be over 65. That means pension spending now eats up more than 9% of Japan’s GDP, with the government spending more on pensions than ever before—about 20% of Japan’s entire economy goes to social security.

But here’s what really gets me: Japan’s got what they call the “Lost Generation” or the “Employment Ice Age.” After Japan’s economic bubble burst in the early 1990s, companies froze hiring and slashed wages. Millions of young graduates got locked out of traditional corporate career tracks and ended up in part-time or temporary jobs without benefits, without job security, and most importantly, without access to the pension system.

Now, 30 years later, this same generation is entering their 40s and 50s with barely any savings, patchy pension contributions, and no stable safety net. When they hit retirement age, Japan could face millions of elderly citizens with almost no pension at all. That’s a terrifying prospect for a country that’s already stretched thin.

To keep the system running, Japan’s had to borrow heavily, pushing public debt to over 250% of GDP—the highest in the developed world. This ain’t sustainable, and everybody knows it.

France: Paying Too Much

France faces a different kind of pressure. At about 14% of GDP, total pension spending in France is currently the third highest among OECD countries after Greece and Italy, with an OECD average of just over 9% Intereconomics. That means every euro spent keeping the pension system running is a euro that can’t go to hospitals, infrastructure, energy, defense, or balancing the national budget.

When President Macron tried to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64 in 2023—a pretty modest reform compared to what other countries are doing—millions of people took to the streets. Garbage piled up in Paris, strikes shut down trains and schools, and Macron’s approval ratings tanked.

Even though France spends more of its GDP on pensions than most other countries, voters saw the reform as a betrayal of a hard-earned right. That’s the political reality leaders are dealing with.

China: The Coming Storm

China’s situation might be the most dramatic of all. Unlike Japan or France, China’s pension system is relatively new, but it’s aging at record speed. Decades of the One Child Policy left China with a narrow base of young workers and a rapidly growing elderly population.

By 2050, nearly 366 million Chinese citizens will be over 65—more than the entire population of the United States today. According to government forecasts, China’s national pension fund could run dry by the early 2030s.

That’s a massive challenge for a country whose people have become accustomed to rapidly improving living standards. Unlike advanced economies, China hasn’t had decades of prosperity to build private savings, so millions of retirees will depend heavily on a system that might not be there when they need it most.

The Political Problem: Why Nobody Fixes It

So if the problem is this obvious, why aren’t governments doing more to fix it?

Simple: every solution comes with short-term pain, and politicians aren’t rewarded for solving long-term problems. That’s why even leaders who can’t agree on anything take the same stance here.

“Social security won’t be touched, other than if there’s fraud or something. It’s going to be strengthened.” — Donald Trump

“If anyone tries to cut social security or Medicare or raise their retirement age, I will stop it.” — Joe Biden

Look, I get it. Fixing pensions means asking people to either work longer, pay more, or get less. None of those options wins elections. In democracies, most leaders think in two to five-year cycles. Pension systems, on the other hand, are 100-year promises. That mismatch between political time and demographic time is why everyone keeps kicking the can down the road.

Let me break down the options they’re avoiding:

Option 1: Raise the Retirement Age

Economically, this makes sense. People live longer, so working a few extra years should help balance the system. But France’s experience shows how difficult this is politically. Even though it’s one of the simplest fixes, it’s politically explosive because people see it as the government moving the goalposts after they’ve already played by the rules for decades.

Option 2: Cut Benefits

Works on paper, but in practice it risks pushing millions of seniors into poverty. In France, nearly a quarter of retirees already rely on their pensions as their only income. In Japan, roughly one in five seniors already lives in relative poverty. Even modest cuts risk pushing hundreds of thousands of people below the poverty line, and inflation is only making things worse.

Option 3: Raise Taxes

If governments can’t cut spending, they raise revenue—usually by asking younger workers to pay more. The problem? Raising payroll taxes hits the exact demographic that’s already squeezed by housing costs, student debt, and inflation. Plus, in places like the UK and Japan, younger generations increasingly doubt they’ll ever see the benefits they’re paying for. And if taxes climb too high, young, mobile workers can simply leave for countries with lower tax burdens.

Option 4: Privatization

Chile tried this back in 1981, replacing its state pension system with private retirement accounts managed by investment firms. For a while, it looked like a success—the model was even praised internationally and inspired pension reforms across Latin America and Eastern Europe.

But over time, cracks appeared. Many workers couldn’t afford to contribute enough, and market downturns slashed returns. The result? Pensions that were far smaller than promised. People took to the streets demanding reform, and the Chilean government eventually had to step back in and guarantee minimum payments, essentially re-socializing the system it had once privatized.

What Actually Works: Countries Getting It Right

Alright, enough doom and gloom. Some countries are actually making progress on this issue, and we can learn from what they’re doing.

Denmark: Automatic Adjustments

In Denmark, the retirement age isn’t a fixed number—it’s tied to life expectancy. As people live longer, the age to qualify for benefits rises automatically. There’s no huge national argument every few years, no reforms that shock the system, just a predictable adjustment that keeps things balanced.

When the rule was announced in 2006, the official retirement age was 65. By 2030, it will rise to 68, and possibly 70 by the early 2040s if lifespans keep increasing. That gives people decades to plan ahead and keeps the system solvent without anyone feeling blindsided.

Germany and the Netherlands have followed similar paths, linking their pension age to demographic data. The retirement age in Germany is currently 66 and will reach 67 by 2031. In the Netherlands, it’s 67 and will automatically adjust with life expectancy.

Sweden: The Model Reform

Sweden’s the one that really gets my attention. Many economists see it as the model for how to reform pensions without political chaos.

Back in the early 1990s, Sweden’s pay-as-you-go model was collapsing under the same demographic pressures we’re seeing everywhere today. Lawmakers realized they had two options: wait for the system to implode or rebuild it entirely. They chose the latter.

Instead of promising fixed benefits forever, Sweden switched to what’s called a notional defined contribution scheme where each worker’s benefits are tied to what they’ve paid in over their lifetime, and payouts automatically adjust if the economy slows or if people live longer American Enterprise Institute. The system just corrects itself over time.

For example, when the global financial crisis hit in 2008, benefits dropped by about 4%. Not ideal, but the system stayed solvent, and because the rules were transparent, there were no riots, no protests, and no panic. People understood the deal they signed up for.

Means Testing and Targeted Support

Some countries are experimenting with means testing, which scales down or cuts pensions for the wealthiest retirees. It’s controversial because it challenges the idea that everyone gets back what they put in, but when budgets are tight, it makes sense to direct the most support to those who truly depend on it.

Australia and Canada both use some form of means testing. In Australia, retirees with high incomes or large superannuation balances lose part of their public pension once they pass a certain threshold. In Canada, the guaranteed income supplement works the same way, topping up pensions for low-income seniors but gradually phasing out as earnings rise.

New Zealand takes a slightly different approach. Everyone over 65 receives a flat pension called New Zealand Superannuation regardless of income, but it’s taxed as regular income, which means wealthier retirees effectively pay a portion back through their higher taxes. It’s simpler and more transparent while still targeting support where it’s needed most.

The Bottom Line

Look, there are no easy answers here, but there are lessons we can take away:

- Countries that act early fare better. Sweden and Denmark show that gradual, automatic adjustments are far less painful than sudden crises.

- Transparency builds trust. People need to believe that the system will still be there for them, that the rules won’t change overnight, and that contributing now will actually mean something later.

- Automatic mechanisms work. Reforms that are transparent, predictable, and fair can go a long way toward building public trust and avoiding political gridlock.

If economics teaches us anything, it’s that the longer you ignore a predictable problem, the more catastrophic it becomes when it finally arrives. Pension systems are ticking time bombs, and governments can’t keep kicking this can down the road forever.

The math doesn’t lie. The worker-to-retiree ratios are collapsing. The trust funds are running dry. And the political incentives all point toward inaction. But some countries have shown that reform is possible if leaders are willing to be honest with their citizens and make tough choices early.

The question isn’t whether pension systems need to change—they do. The question is whether we’ll address the problem now with manageable reforms, or wait until we’re forced into crisis mode with nowhere left to turn.

Stay sharp out there.

—Van

Sources: Social Security Administration, Congressional Budget Office, OECD Pension Data, Urban Institute Social Security Analysis, Sweden Government Pension Reform